On this 11th anniversary of 9/11, it’s a good day for us to look back and assess the damage.

On this 11th anniversary of 9/11, it’s a good day for us to look back and assess the damage.

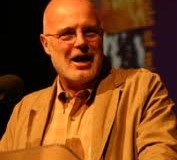

[Brian McLaren, The Huffington Post, 9.11.2012] The damage to buildings long been accounted for, and much has been rebuilt. The damage to the economy has also been debated and estimated — and replaced by new, greater, primarily self-inflicted economic wounds.

The damage to families is, of course, impossible to assess or quantify. It can only be mourned.

But there’s another impact of those attacks that is still too seldom tallied: how our religious communities have turned from their deepest teachings and values of peace and reconciliation, and have too often become possessed, we might say, by spirits of fear, revenge, isolation and hostility.

As a Christian, I’ve certainly seen it and felt it in the Christian community, expressed often in a sense that the more you love Jesus, the more inhospitable you’ll be toward other faiths. “Don’t let them build mosques or temples on our turf,” some say. “Don’t let them express their difference in dress or ritual,” others suggest. “Require them to conform to our holidays and cultural codes,” others demand.

This turn toward hostility has disturbed me, so a few years ago I began studying it more in earnest. My research led me to the underlying relationships among religious hostility, religious solidarity and religious identity. Today, the results of my research and reflection go public in a new book (“Why Did Jesus, Moses, the Buddha, and Mohammed Cross the Road?“), and among many conclusions, one stands out — one that I hope my fellow Christians can hear and ponder.

To be a strong Christian does not mean you have to have a strong antipathy toward other faiths and their leaders.

To be hostile rather than hospitable, in fact, makes you a worse Christian, not a better one.

To be respectful, curious, humble, inquisitive and hospitable to people of other faiths makes you a better Christian — meaning a more Christ-like one. To love your neighbor means, at the very least, not to discriminate against him, not to dehumanize him, not to insult him or what he holds dear, not to act as if God made a mistake in giving him a place in this world.

Put more positively, to love your neighbor of another faith means to seek to understand her, to learn to see the world from her perspective, to stand with her, as it were, so that you can feel what she feels and maybe even come to understand why she loves what she loves.

In the book I recount a conversation I shared over lunch with an imam who became a good friend in the weeks after 9/11. We each shared what it was we loved about our religions and their founders. He went first, and then as I was sharing, he interrupted me. “I have never heard a Christian share what he loves about his faith,” he told me. “I have only heard my fellow Muslims tell me what Christians believe. It is so different to hear it from you.”

I knew what he meant.

What would happen if more of us, whatever our religious tradition, extracted ourselves from the vicious cycles of offense and revenge, hurt and resentment, misunderstanding and counter-misunderstanding, rumor and innuendo? One thing is certain: We would become more faithful to the vision of our founders, not less. May that be so.