The Pew Forum – Feb. 17, 2010

The Pew Forum – Feb. 17, 2010

Introduction and Overview

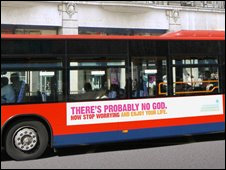

By some key measures, Americans ages 18 to 29 are considerably less religious than older Americans. Fewer young adults belong to any particular faith than older people do today. They also are less likely to be affiliated than their parents’ and grandparents’ generations were when they were young. Fully one-in-four members of the Millennial generation – so called because they were born after 1980 and began to come of age around the year 2000 – are unaffiliated with any particular faith. Indeed, Millennials are significantly more unaffiliated than members of Generation X were at a comparable point in their life cycle (20% in the late 1990s) and twice as unaffiliated as Baby Boomers were as young adults (13% in the late 1970s). Young adults also attend religious services less often than older Americans today. And compared with their elders today, fewer young people say that religion is very important in their lives.

Yet in other ways, Millennials remain fairly traditional in their religious beliefs and practices. Pew Research Center surveys show, for instance, that young adults’ beliefs about life after death and the existence of heaven, hell and miracles closely resemble the beliefs of older people today. Though young adults pray less often than their elders do today, the number of young adults who say they pray every day rivals the portion of young people who said the same in prior decades. And though belief in God is lower among young adults than among older adults, Millennials say they believe in God with absolute certainty at rates similar to those seen among Gen Xers a decade ago. This suggests that some of the religious differences between younger and older Americans today are not entirely generational but result in part from people’s tendency to place greater emphasis on religion as they age.

In their social and political views, young adults are clearly more accepting than older Americans of homosexuality, more inclined to see evolution as the best explanation of human life and less prone to see Hollywood as threatening their moral values. At the same time, Millennials are no less convinced than their elders that there are absolute standards of right and wrong. And they are slightly more supportive than their elders of government efforts to protect morality, as well as somewhat more comfortable with involvement in politics by churches and other houses of worship.

These and other findings are discussed in more detail in the remainder of this report by the Pew Research Center’s Forum on Religion & Public Life. It explores the degree to which the religious characteristics and social views of young adults differ from those of older people today, as well as how Millennials compare with previous generations when they were young.

Religious Affiliation

Compared with their elders today, young people are much less likely to affiliate with any religious tradition or to identify themselves as part of a Christian denomination. Fully one-in-four adults under age 30 (25%) are unaffiliated, describing their religion as “atheist,” “agnostic” or “nothing in particular.” This compares with less than one-fifth of people in their 30s (19%), 15% of those in their 40s, 14% of those in their 50s and 10% or less among those 60 and older. About two-thirds of young people (68%) say they are members of a Christian denomination and 43% describe themselves as Protestants, compared with 81% of adults ages 30 and older who associate with Christian faiths and 53% who are Protestants.

The large proportion of young adults who are unaffiliated with a religion is a result, in part, of the decision by many young people to leave the religion of their upbringing without becoming involved with a new faith. In total, nearly one-in-five adults under age 30 (18%) say they were raised in a religion but are now unaffiliated with any particular faith. Among older age groups, fewer say they are now unaffiliated after having been raised in a faith (13% of those ages 30-49, 12% of those ages 50-64, and 7% of those ages 65 and older).

Young people’s lower levels of religious affiliation are reflected in the age composition of major religious groups, with the unaffiliated standing out from other religious groups for their relative youth. Roughly one-third of the unaffiliated population is under age 30 (31%), compared with 20% of the total population.

Data from the General Social Surveys (GSS), which have been conducted regularly since 1972, confirm that young adults are not just more unaffiliated than their elders today but are also more unaffiliated than young people have been in recent decades. In GSS surveys conducted since 2000, nearly one-quarter of people ages 18-29 have described their religion as “none.” By comparison, only about half as many young adults were unaffiliated in the 1970s and 1980s.

Among Millennials who are affiliated with a religion, however, the intensity of their religious affiliation is as strong today as among previous generations when they were young. More than one-third of religiously affiliated Millennials (37%) say they are a “strong” member of their faith, the same as the 37% of Gen Xers who said this at a similar age and not significantly different than among Baby Boomers when they were young (31%).

Worship Attendance

In the Pew Forum’s 2007 Religious Landscape Survey, young adults report attending religious services less often than their elders today. One-third of those under age 30 say they attend worship services at least once a week, compared with 41% of adults 30 and older (including more than half of people 65 and older). But generational differences in worship attendance tend to be smaller within religious groups (with the exception of Catholics) than in the total population. In other words, while young people are less likely than their elders to be affiliated with a religion, among those who are affiliated, generational differences in worship attendance are fairly small.

The long-running GSS also finds that young people attend religious services less often than their elders. Furthermore, Millennials currently attend church or worship services at lower rates than Baby Boomers did when they were younger; 18% of Millennials currently report attending religious services weekly or nearly weekly, compared with 26% of Boomers in the late 1970s. But Millennials closely resemble members of Generation X when they were in their 20s and early 30s, when one-in-five Gen Xers (21%) reported attending religious services weekly or nearly weekly.

Other Religious Practices

Consistent with their lower levels of affiliation, young adults engage in a number of religious practices less often than do older Americans, especially the oldest group in the population (those 65 and older). For example, the 2007 Religious Landscape Survey finds that 27% of young adults say they read Scripture on a weekly basis, compared with 36% of those 30 and older. And one-quarter of adults under 30 say they meditate on a weekly basis (26%), compared with more than four-in-ten adults 30 and older (43%). These patterns hold true across a variety of religious groups.

In addition, less than half of adults under age 30 say they pray every day (48%), compared with 56% of Americans ages 30-49, 61% of those in their 50s and early 60s, and more than two-thirds of those 65 and older (68%). Age differences in frequency of prayer are most pronounced among members of historically black Protestant churches (70% of those under age 30 pray every day, compared with 83% among older members) and Catholics (47% of Catholics under 30 pray every day, compared with 60% among older Catholics). The differences are smaller among evangelical and mainline Protestants.

Although Millennials report praying less often than their elders do today, the GSS shows that Millennials are in sync with Generation X and Baby Boomers when members of those generations were younger. In the 2008 GSS survey, roughly four-in-ten Millennials report praying daily (41%), as did 42% of members of Generation X in the late 1990s. Baby Boomers reported praying at a similar rate in the early 1980s (47%), when the first data are available for them. GSS data show that daily prayer increases as people get older.

Religious Attitudes and Beliefs

Less than half of adults under age 30 say that religion is very important in their lives (45%), compared with roughly six-in-ten adults 30 and older (54% among those ages 30-49, 59% among those ages 50-64 and 69% among those ages 65 and older). By this measure, young people exhibit lower levels of religious intensity than their elders do today, and this holds true within a variety of religious groups.

Gallup surveys conducted over the past 30 years that use a similar measure of religion’s importance confirm that religion is somewhat less important for Millennials today than it was for members of Generation X when they were of a similar age. In Gallup surveys in the late 2000s, 40% of Millennials said religion is very important, as did 48% of Gen Xers in the late 1990s. However, young people today look very much like Baby Boomers did at a similar point in their life cycle; in a 1978 Gallup poll, 39% of Boomers said religion was very important to them.

Similarly, young adults are less convinced of God’s existence than their elders are today; 64% of young adults say they are absolutely certain of God’s existence, compared with 73% of those ages 30 and older. In this case, differences are most pronounced among Catholics, with younger Catholics being 10 points less likely than older Catholics to believe in God with absolute certainty. In other religious traditions, age differences are smaller.

But GSS data show that Millennials’ level of belief in God resembles that seen among Gen Xers when they were roughly the same age. Just over half of Millennials in the 2008 GSS survey (53%) say they have no doubt that God exists, a figure that is very similar to that among Gen Xers in the late 1990s (55%). Levels of certainty of belief in God have increased somewhat among Gen Xers and Baby Boomers in recent decades. (Data on this item stretch back only to the late 1980s, making it impossible to compare Millennials with Boomers when Boomers were at a similar point in their life cycle.)

Differences between young people and their elders today are also apparent in views of the Bible, although the differences are somewhat less pronounced. Overall, young people are slightly less inclined than those in older age groups to view the Bible as the literal word of God. Interestingly, age differences on this item are most dramatic among young evangelicals and are virtually nonexistent in other groups. Although younger evangelicals are just as likely as older evangelicals (and more likely than people in most other religious groups) to see the Bible as the word of God, they are less likely than older evangelicals to see it as the literal word of God. Less than half of young evangelicals interpret the Bible literally (47%), compared with 61% of evangelicals 30 and older.

On this measure, too, Millennials display beliefs that closely resemble those of Generation X in the late 1990s. In the 2008 GSS survey, roughly a quarter of Millennials (27%) said the Bible is the literal word of God, compared with 28% among Gen Xers when they were young. This is only slightly lower than among Baby Boomers in the early 1980s (33%) and is very similar to the 29% of Boomers in the late 1980s who said they viewed the Bible as the literal word of God.

On still other measures of religious belief, there are few differences in the beliefs of young people compared with their elders today. Adults under 30, for instance, are just as likely as older adults to believe in life after death (75% vs. 74%), heaven (74% each), hell (62% vs. 59%) and miracles (78% vs. 79%). In fact, on several of these items, young mainline Protestants and members of historically black Protestant churches exhibit somewhat higher levels of belief than their elders.

Young people who are affiliated with a religion are more inclined than their elders to believe their own religion is the one true path to eternal life (though in all age groups, more people say many religions can lead to eternal life than say theirs is the one true faith). Nearly three-in-ten religiously affiliated adults under age 30 (29%) say their own religion is the one true faith leading to eternal life, higher than the 23% of religiously affiliated people ages 30 and older who say the same. This pattern is evident among all three Protestant groups but not among Catholics.

Interestingly, while more young Americans than older Americans view their faith as the single path to salvation, young adults are also more open to multiple ways of interpreting their religion. Nearly three-quarters of affiliated young adults (74%) say there is more than one true way to interpret the teachings of their faith, compared with 67% of affiliated adults ages 30 and older.

Social and Culture War Issues

Young people are more accepting of homosexuality and evolution than are older people. They are also more comfortable with having a bigger government, and they are less concerned about Hollywood threatening their values. But when asked generally about morality and religion, young adults are just as convinced as older people that there are absolute standards of right and wrong that apply to everyone. Young adults are also slightly more supportive of government efforts to protect morality and of efforts by houses of worship to express their social and political views.

According to the 2007 Religious Landscape Survey, almost twice as many young adults say homosexuality should be accepted by society as do those ages 65 and older (63% vs. 35%). Young people are also considerably more likely than those ages 30-49 (51%) or 50-64 (48%) to say that homosexuality should be accepted. Stark age differences also exist within each of the major religious traditions examined. Compared with older members of their faith, significantly larger proportions of young adults say society should accept homosexuality.

In the 2008 GSS survey, just over four-in-ten (43%) Millennials said homosexual relations are always wrong, similar to the 47% of Gen Xers who said the same in the late 1990s. These two cohorts are significantly less likely than members of previous generations have ever been to say that homosexuality is always wrong. The views of the various generations on this question have fluctuated over time, often in tandem.

Roughly half of young adults (52%) say abortion should be legal in all or most cases. On this issue, young adults express slightly more permissive views than do adults ages 30 and older. However, the group that truly stands out on this issue is people 65 and older, just 37% of whom say abortion should be legal in most or all cases.

Interestingly, this pattern represents a significant change from earlier polling. Previously, people in the middle age categories (i.e., those ages 30-49 and 50-64) tended to be more supportive of legal abortion, while the youngest and oldest age groups were more opposed. In 2009, however, attitudes toward abortion moved in a more conservative direction among most groups in the population, with the notable exception of young people. The result of this conservative turn among those in the 30-49 and 50-64 age brackets means that their views now more closely resemble those of the youngest age group, while those in the 65-and-older group now express the most conservative views on abortion of any age group.

Surveys also show that large numbers of young adults (67%) say they would prefer a bigger government that provides more services over a smaller government that provides fewer services. Among older Americans, only 41% feel this way. Fewer young people than older people see their moral values as under assault from Hollywood; one-third of adults under age 30 agree that Hollywood and the entertainment industry threatens their values, compared with 44% of people 30 and older. And more than half of young adults (55%) believe that evolution is the best explanation for the development of human life, compared with 47% of people in older age groups. These patterns are seen both in the total population and within a variety of religious traditions, though the link between age and views on evolution is strongest among Catholics and members of historically black Protestant churches.

But differences between young adults and their elders are not so stark on all moral and social issues. For instance, more than three-quarters of young adults (76%) agree that there are absolute standards of right and wrong, a level nearly identical to that among older age groups (77%). More than half of young adults (55%) say that houses of worship should speak out on social and political matters, slightly more than say this among older adults (49%). And 45% of young adults say that the government should do more to protect morality in society, compared with 39% of people ages 30 and older.

GSS surveys show Millennials are more permissive than their elders are today in their views about pornography, but their views are nearly identical to those expressed by Gen Xers and Baby Boomers when members of those generations were at a similar point in their life cycles. About one-in-five Millennials today say pornography should be illegal for everyone (21%), similar to the 24% of Gen Xers who said this in the late 1990s and the 22% of Boomers who took this view in the late 1970s. Data for the Silent and Greatest generations at similar ages are not available, but data from the 1970s onward suggest that people become more opposed to pornography as they age.

Similarly, Millennials at the present time stand out from other generations for their opposition to Bible reading and prayer in schools, but they are less distinctive when compared with members of Generation X or Baby Boomers at a comparable age. During early adulthood, about half of Boomers (51%) and Gen Xers (54%) said they approved of U.S. Supreme Court rulings that banned the required reading of the Lord’s Prayer or Bible verses in public schools; 56% of Millennials took this view in 2008. Generation X and the Boomer generation have become less supportive of the court’s position over time, while the pattern in the views of the Silent and Greatest generations has been less clear.

More Information

For other treatments of religion among young adults in the U.S. and how they compare with older generations, see, for example, Souls in Transition: The Religious and Spiritual Lives of Emerging Adults by Christian Smith and Patricia Snell (2009) and After the Baby Boomers: How Twenty- and Thirty-Somethings Are Shaping the Future of American Religion by Robert Wuthnow (2007).

Download the appendix: Selected Religious Beliefs and Practices among Ages 18-29 by Decade (1-page PDF)

Download the full report (29-page PDF)

This analysis was written by Allison Pond, Research Associate; Gregory Smith, Senior Researcher; and Scott Clement, Research Analyst, Pew Forum on Religion & Public Life.

Five centuries before Facebook and the Arab spring, social media helped bring about the Reformation

Five centuries before Facebook and the Arab spring, social media helped bring about the Reformation