You can call them respectable democracies, but India, Brazil, and South Africa will be judged by how they act abroad. And on the Syria question, it’s been shameful.

You can call them respectable democracies, but India, Brazil, and South Africa will be judged by how they act abroad. And on the Syria question, it’s been shameful.

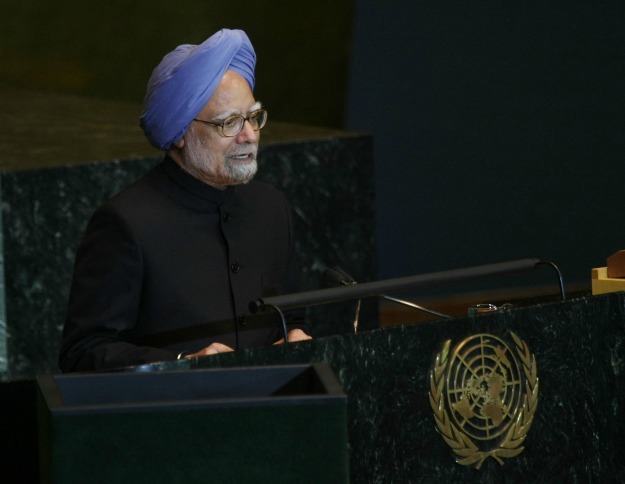

[By James Traub* |Â Foreign Policy |Â March 9, 2012]Â As global power has shifted away from the West, the emerging order has come to be identified with the BRICS — an unofficial geopolitical bloc consisting of Brazil, Russia, India, China, and South Africa. But the BRICS are equally divided between autocratic and democratic states. The growing reach of powerful autocracies is nothing to celebrate, but the rise of stable and increasingly prosperous democracies in the developing world — India, Brazil, South Africa, Turkey, and Indonesia, among others — has been the single most encouraging phenomenon in the world over the last generation. Those first three countries, in fact, have established an informal bloc known as IBSA. This, too, should be a profoundly welcome development. But it hasn’t been, at least in Western capitals. In global affairs, it turns out, emerging democracies often behave a lot like Third World autocracies. And IBSA is turning out to be not so very different from the BRICS.

In a fascinating real-world laboratory experiment, all three IBSA countries served on the United Nations Security Council in 2011; India and South Africa remain on the council this year. All three were thus forced to take a position during the hugely contentious debates on military intervention in Libya and political intervention in Syria. The result has not been edifying, at least from the viewpoint of Arab and Western publics. India and Brazil abstained from Resolution 1973 authorizing the NATO operation in Libya, and all three refused to vote for a draft resolution last October condemning the “grave and systematic human rights violations” committed by Syrian security forces against civilians. India and South Africa did, however, vote for a similar resolution this February, which Russia and China — the other BRICS members on the council this year — vetoed.

This week, I met with Hardeep Singh Puri, India’s ambassador to the United Nations. For those who knew his predecessor, Nirupam Sen, a hard-left Bengali Brahmin prone to delivering windy and condescending lectures before gumming up the works of the day’s debate, Puri, a blunt and hard-headed Sikh, constitutes a very welcome change in the diplomatic weather. But diplomats and human rights experts say that, throughout 2011, India sought to block efforts by the United States, France, and Britain to raise Syria’s growing assault on civilians in the Security Council, provoking some very ill will. “They were,” says a diplomat from one of the five permanent members of the Security Council, “obstructive and not helpful.”

When I asked Puri why he had declined to endorse the resolution last October, he pointed out that as president of the Security Council a few months earlier, he had written a “presidential statement” with almost identical language. He was making an active effort to stop the violence, he said. But the October resolution was unacceptable because it referred to Article 41 of the U.N. Charter, which authorizes the use of sanctions and other coercive measures. It sounded like a flimsy rationale because the measure made only passing reference to Article 41. More to the point, India, like Russia, took the position that the council had no business trying to coerce Syrian President Bashar al-Assad by any means at all to stop the killing. In the official explanation of his vote, Puri said, “While the right of people to protest peacefully is to be respected, states cannot but take appropriate action when militant groups, heavily armed, resort to violence against state authority and infrastructure.”

I was aghast when I ran across this statement, which parroted Damascus’s own grossly cynical line. I asked Puri whether he still believed that, to which he said, “If the protests are peaceful, why would you want to use weapons against them?” Syrian forces would never fire on unarmed protesters. This was the kind of language Chinese diplomats used to deploy to explain their defense of Khartoum during Security Council debates over Darfur. Had India adopted China’s skewed view of international human rights law?

It’s precisely because the IBSA countries are respectable democracies that they can prove so useful to the less respectable. Philippe Bolopion, the U.N. director for Human Rights Watch, says, “For months, they enabled Russia and China to use their veto and block any Security Council action.” It was far easier for the veto-bearing countries to claim that they were acting out of principle when they had India and others on their side. Of course, Russia and China wielded their vetoes again last month when India and South Africa shifted their votes, but it’s striking that, since that time, both Moscow and Beijing have sought to distance themselves from Damascus. They’ve lost their cover.

India’s behavior served the cynicism of others, but it was not, itself, altogether cynical. Unlike Russia, India has no real political or economic interests in Syria (or Libya). What is has are ideological reflexes left over from the era of the “Non-Aligned Movement,” of which it was a founder. C. Raja Mohan, a leading Indian foreign-policy commentator, recently ascribed India’s Syria policy to its long-standing preoccupation with “the anti-colonial theme” and to “solidarity” with the Arabs against Israel. Countries like India that long chafed under imperial dominion tend to see the West’s moral activism as a new species of colonialism. India is thus a zealous defender of the principle of state sovereignty and reflexively opposes any intrusion into it. Puri says that he feared that the West was looking for an excuse to go to war in Syria, as it had in Libya, but Article 41 only authorizes the use of nonmilitary forms of coercion. He wasn’t standing up to “humanitarian intervention” in Syria, which in any case had zero support in Western capitals last fall; he was defending Syria’s right to do as it wished to its own citizens.

Why did India change its vote last month? Puri says that the resolution, which endorsed an Arab League plan designed to ease Assad from power, included a specific proviso excluding the possibility of military action. But Russia and China saw the new resolution as little different from the previous one and vetoed it too, implicitly defending their own right to do as they wish to their citizens, whether in Chechnya or Tibet. (India, too, is loath to set a precedent that could later justify Security Council action in Kashmir.) David Malone, a senior Canadian diplomat and the author of Does the Elephant Dance?, a book on Indian foreign policy, suggests a less legalistic explanation for the Feb. 4 vote: Once the violence grew worse and the Arab League more strident, domestic public opinion, in the form of pundits like Mohan, forced New Delhi’s hand and persuaded it to look beyond the obsession with sovereignty. In this regard, of course, the IBSA countries do resemble the Western democracies: Policy responds to public opinion. Russia and China can smother or ignore the public in a way that India and Brazil cannot.

This raises the intriguing question of where the IBSA countries, as well as other emerging democracies, are heading. It’s hard to predict. As one Western diplomat put it, anti-colonialism is in South Africa’s “founding myth,” and the reflexes associated with it will not quickly subside. Brazil, on the other hand, seemed far less comfortable defending Syria than India or South Africa, perhaps because Brazilian public opinion is more open to Western norms. All these countries have been wary of the principle that states have a “responsibility to protect” (R2P) their citizens from mass atrocities, as well as an obligation to act on behalf of people threatened with atrocities elsewhere. Puri says that India accepts the first part, but thinks that the second “needs to be addressed.” But with Arab states like Qatar citing “R2P” to justify action in Libya and Syria, public opinion in non-Western democracies may begin to move beyond the anti-neocolonial reflex.

All three IBSA countries are candidates for permanent membership in the Security Council. Puri says that he is confident — it’s not clear why — that India, at least, will gain that status soon. He is not troubled, he says, by the thought that giving aid and comfort to Russia and China will harm India’s candidacy with the United States, Britain, and France, which could block it. One of the fundamental questions about the post-Western world we are moving toward is whether countries like India will be “socialized” to Western norms or whether things will work the other way around. The legatees of that system, above all in the United States, will feel a great deal more comfortable about the prospect of sharing power if the newcomers accept the obligations understood to come with that power.

Originally posted here.

* James Traub is a fellow of the Center on International Cooperation. “Terms of Engagement,” his column for ForeignPolicy.com, runs weekly.